In many of our previous articles, we talked about how ODI cricket has drastically changed throughout the years.

- In the 70s, an average player batting in the top 7 used to average 27.37 by striking at less than 62 in ODI cricket; in the last decade, the average rose to 33.83, and now the scoring rate is 82.92.

- 430 runs were scored in an average ODI match in the 2010s; for the 70s, the same number went down to 345.

The change is simply enormous, the result of some significant differences.

This article aims to describe some of these changes by illustrating some of the key events and players that shaped ODI batting into what it is today.

The WSC Revolution

In 1977, Kerry Packer introduced World Series Cricket (WSC) with revolutionary ideas such as floodlit matches, white-coloured balls, and coloured kits, which changed the course of cricket forever.

At its inception, Packer wasn’t allowed to use any of the traditional cricket grounds in the country and had to resort to hosting his matches at non-cricket grounds, which gravely affected the popularity of WSC as people remained uncertain about the quality of the pitches in these grounds.

In a bid to increase viewership, Packer experimented with the idea of day-night matches under floodlights.

This bold move, later regarded by legendary commentator Tony Grieg as a masterstroke, brought unprecedented changes in the promotion and coverage of cricket and drastically improved the game’s popularity in the coming years.

This novel approach required a different kind of ball, as red-coloured balls would have limited visibility in the night sky, and this fostered the use of white balls, which have since become the standard choice for a limited-over game.

Tight schedules and exceptional competition meant that players became fitter and more skilled, resulting in higher-quality cricket being played.

Other innovations include the implementation of fielding circles and the first widespread use of helmets. All these additions and changes have ensured that the impact and legacy of the World Series Cricket last forever.

The 80s: The Decade of Greats

The 80s were cluttered with batting and bowling talent alike. Within this sea of talent, three names stand out for their invaluable contribution to the development of batting in ODI cricket.

The first and most prominent name is Sir Vivian Richards, the King and the original Master Blaster.

With scything cuts and devastating pulls, he unleashed a wave of unprecedented terror among captains and bowlers alike, all while nonchalantly chewing his gum, emanating an aura of unmatched swagger.

The second name is that of Zaheer Abbas, one blessed with equally good timing and divine stroke play.

He drove with surgical precision and found seemingly nonexistent gaps with prolific ease. Both players had impossible strike rates compared to their era.

They set standards, admittedly impossible standards for that time, but standards nevertheless inspired players around the world.

Players were more confident in playing their shots, and although they weren’t quite as successful, the change in mindset was enough to amplify strike rates worldwide.

The last name was neither as destructive as Viv Richards nor as refined as Zaheer Abbas.

However, he was just as effective by simply picking the gaps and using the large boundaries to his advantage.

Dean Jones retired with the third-highest average in ODI cricket, and although this landmark has been breached by many since then, his style of play will forever remain etched in cricketing history.

He redefined the art of running between the wickets as he regularly tapped the ball into gaps with soft hands and stole extra runs from right under the nose of the fielder.

This rotation of strikes allowed the smooth flow of an innings, safely releasing all the pressure built by the opposition as they felt the game slipping away from them with every passing run.

His free-flowing nature was adopted and acknowledged by many contemporaries and future greats as a highly effective method for a run chase. Middle-order batters strived to achieve his level of running, in turn making them fitter and better players.

Jayasuriya and the Powerplay

Powerplay was another indirect product of the World Series Cricket.

Although field restrictions were first used in South African domestic cricket, the WSC brought the idea into the spotlight.

Field restrictions were first introduced to allow batsmen to hit more boundaries and take more risks which can spice up the game and hence increase viewership.

For example, in a close match where 15 runs are needed off 6 balls, the bowler could simply push all his fielders to the boundary and ensure that the batsman’s hands are tied, and more often than not, this guaranteed the victory of the bowling team.

Field restrictions were meant to dull this edge of the bowlers.

Eventually, field restrictions found their way to the mainstream game, and soon no more than 2 fielders were allowed outside the 30-yard circle for the first 15 overs and then 5 fielders for the rest of the game.

However, the exceptional quality of pace bowling of that era combined with pitches that generally favoured bowlers meant that sometimes the field restrictions had the opposite effect on batsmen, where they stopped taking risks in the powerplay and instead tried to survive through the first phase of 15 overs, as even a slight error of judgment can result in the batsman losing his wicket to a catch at gully, covers or short midwicket.

This effect was exponentially increased due to the prowess of legendary bowlers such as Malcolm Marshall, Wasim Akram, Waqar Younis, Craig McDermott, and the all-rounder quartet of that era, who, when coupled with the bowling perks of the new ball, produced devastating spells at great frequency.

However, where most batsmen saw a testing period laced with deadly bowlers and a close-knit of prowlers waiting to gobble up any edges from innocent pokes or naive cover drives, one captain saw an opportunity.

During the 1992 World Cup, the revolutionary Kiwi captain, Martin Crowe, sent Mark Greatbatch, who usually batted at 5, to open the innings.

He told him to be “positive and generate some momentum”.

This move turned out to be a masterstroke as the burly left-hander tonked the ball to all parts of the ground in brute fashion, taking complete advantage of the field restrictions.

New Zealand went on to reach the semifinals: one of the critical reasons for this was the exploitation of powerplay.

However, in the next edition of the World Cup, the cricketing world indeed beheld the full potential of this tactic.

Sri Lanka was rocked by a bomb attack, and its cricket board was reeling on the shores of bankruptcy when it entered the World Cup of 96.

Hence, there were few who gave them any chance of reaching the playoffs, let alone winning the prized trophy.

However, what transpired next was an extraordinary show of grit, resolve, and camaraderie, which ended with Sri Lanka being crowned the World Champions.

Captain Ranatunga and newly appointed coach Dav Whatmore designed elaborate and precise plans specifically for the tournament, one of which was to open with the pair, Jayasuriya-Kaluwitharna.

Jayasuriya and Kaluwitharna, both lower-order batters before the World Cup, were sent up the order to fully use the powerplay restrictions.

They were both given the insurance to go after the bowling and the captain’s protection, who promised not to drop them.

With their positions secure, both batsmen unleashed a wave of fury and destruction, the likes of which had never been seen before. They cut and pulled and drove and slogged, never letting the opposition settle and wearing down the bowlers and fielders both physically and mentally.

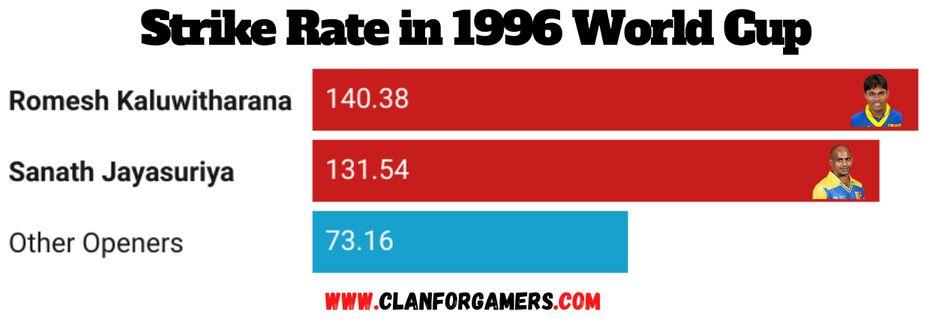

At a time when 250 was considered a daunting total, Sri Lanka passed 100 runs thrice in 6 innings before the end of the powerplay, with Jayasuriya scoring 221 runs at a stunning strike rate of 132.

He was awarded the man of the tournament, after which he continued to open the innings and scored a truckload of runs at a brisk rate.

He revolutionized powerplay batting and took ball striking to a whole new level, paving the way for the emergence of many other aggressive openers such as Adam Gilchrist, Virender Sehwag, and Herschelle Gibbs.